Highway to Hell

The unheard voices of Brazil's forgotten children

Welcome to Brazil

A country of colour and sunshine,

from the Rio carnival to the Amazon rainforest

Boasting the 8th-highest GDP in the world, Brazil was a founding member of the UN.

It is considered an emerging global power, thriving on industry, trade, and tourism.

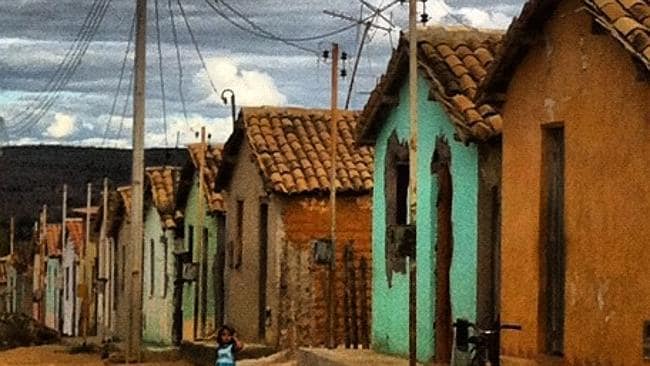

A street in Medina

A street in Medina

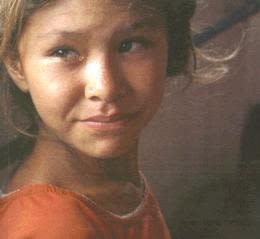

Lilian, in her favourite top

Lilian, in her favourite top

Lilian was just ten the first time. An enormous forty-tonne truck pulled up outside the small brick shack she lived in with her mother in Medina, a small, rural town in Minas Gerais state, Brazil. It wasn’t that easy to get to her house through the narrow, cobbled maze of Medina’s back streets, but here he was.

Her mother arrived home shortly after, on foot, and spoke to the driver. Then she pulled Lilian out of the house, shoving her roughly towards the open truck door.

“Make sure he gives you the money!” she called after her.

He did give her the money, once he had had his way with her, and pushed her out of the cabin onto the street, a long way below.

So did the next truck that came, and the next. They all knew the way to her house, somehow, sounding the horn and waiting for her to come out and make the terrifying climb up into the cabin.

Sometimes she tried to refuse, but her mother would push her out of the door, and not let her back in until she had the money.Nobody batted an eyelid at the preteen girl in her skimpy dress - it was normal in Medina.

She got pregnant, but lost the baby, which she insisted to everyone happened when she fell off a motorbike. Some suspected she had been forced into a backstreet abortion, but no-one knew for sure.

Her mother ran off with a boyfriend when she was twelve, and she moved in with her ‘grandmother’, an older neighbour who wasn’t actually related to her. She sent Lilian out to the bar across the road, to dance for the men and earn her rent in money or shorts of cachaça rum from the men.

Lilian didn’t mind; she expected it. What else was there? She had been used, and then discarded all her life.

Sometimes, she would run away, disappearing off with other girls her age, taking a truck down the motorway and ending up hundreds of miles away in a roadside brothel.

Other times, a relative or neighbour would take her with them on a trip, using her as a bargaining chip - a ride to the next town, a plate of food, or somewhere to sleep for the night; they could get everything they needed with a pretty twelve-year-old to offer in exchange.

Once, she was in a bar and got stabbed in the back during a fight. She was terrified, sure she was going to die as she passed out on the floor.

She woke up in hospital, stitches in the wound just below her neck. The doctor told her if it had been half an inch either way, she wouldn’t have woken up at all.

She still held onto her dreams, though. She wanted to be a lawyer, a public prosecutor. She often wore a black one-shoulder top, with the words of a Latin proverb, ‘Let justice be done, though the world perish’ printed on the back.

Brazil has the second-highest rates in the world for child prostitution, and girls - because it is always the girls, who are seen as less valuable - as young as nine years old are commonly found working the streets.

Despite the wealth and prosperity of Brazil’s cities, many rural Brazilians live in desperate poverty.

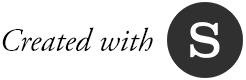

The BR-116 highway, a pale scar which cuts through the landscape for nearly 3,000 miles along Brazil’s eastern coast, is the sole source of income for hundreds of small rural communities.

Men work away from home in the dirt and danger of the granite mines, while many of the women turn to prostitution to keep bread - or more often, rice - on the table.

The highway has earned the moniker ‘Highway to Hell’ because every 10 miles, on average, there is a truck stop where child sex is sold, for as little as £8 a time.

Many girls are sent out to the motorway by their parents, to earn enough to feed the family. Sometimes a mother might negotiate the price, before sending her daughters to be abused.

In other places, three generations of the same family can be found selling sex - a 10-year-old girl, her 27-year-old mother, and her 45-year-old grandmother, competing for the attentions of the truckers.

In the rural communities of Minas Gerais and Bahia State, the two Brazilian states worst-affected by child sexual abuse, prostitution is one of the only jobs going. There is little other opportunity for work, and even less without education - most of the girls drop out of school around age 10, as they are too tired after being up on the motorway all night.

Child prostitution is just a way of life in the small towns along the BR-116. No one is shocked to see a twelve-year-old girl standing at the side of the road, advertising her preteen body for sale.

Everybody knows somebody whose young daughter is doing ‘programmes’ - their euphemism for a paid sexual encounter - in a roadside brothel.

A baby girl represents a future income, and sending a daughter out for her first ‘programme’ is as normal as her playing with her first Barbie doll.

The authorities are overwhelmed by the scale of the problem, so they choose to ignore it - the social services department of Cândido Sales, the next town up from Medina, categorically denies there being a single case in the last 10 years, despite the Children's Council in the same town filing new reports of the cases almost every day.

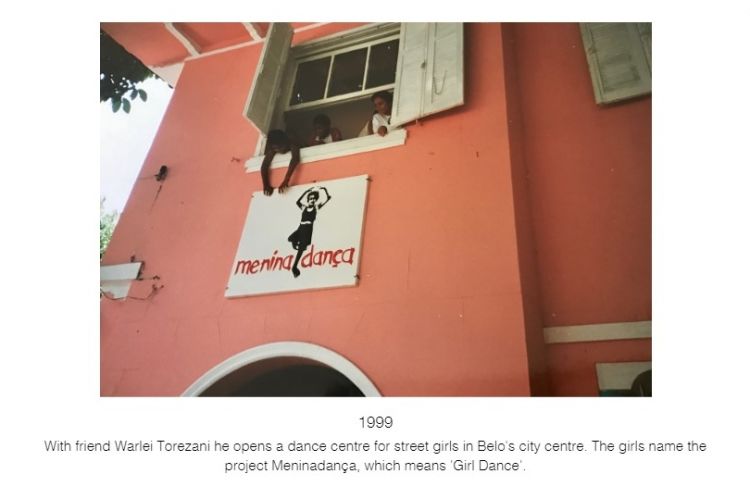

From the Meninadança website

From the Meninadança website

The cover image of 'Street Girls', the book Matt wrote about this time.

The cover image of 'Street Girls', the book Matt wrote about this time.

Warlei Torezani

Warlei Torezani

From the Meninadança website

From the Meninadança website

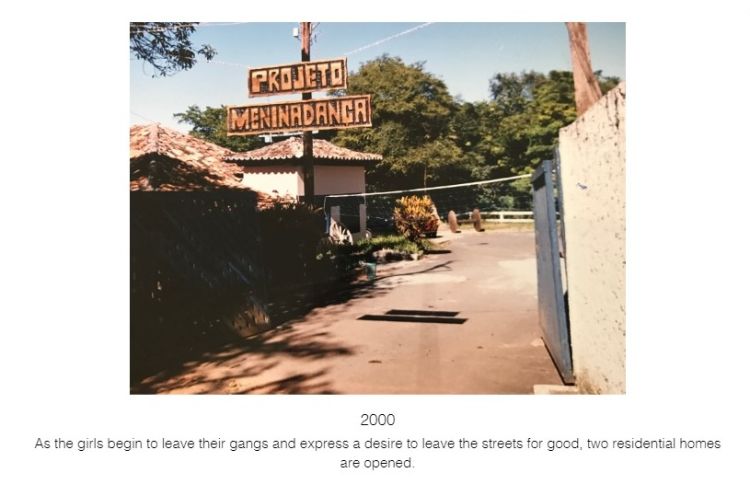

From the Meninadança website

From the Meninadança website

Matt's facebook post from the day he got back in touch with Bruna, the girl he saved from the streets.

Matt's facebook post from the day he got back in touch with Bruna, the girl he saved from the streets.

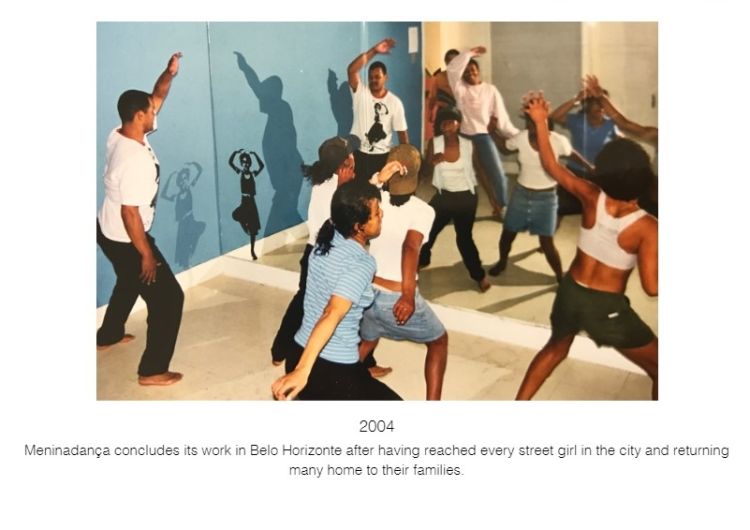

From the Meninadança website

From the Meninadança website

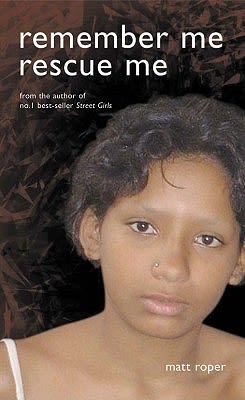

'Remember Me, Rescue Me' by Matt Roper, the book which sparked Dean Brody's interest in Brazil.

'Remember Me, Rescue Me' by Matt Roper, the book which sparked Dean Brody's interest in Brazil.

Dean Brody

Dean Brody

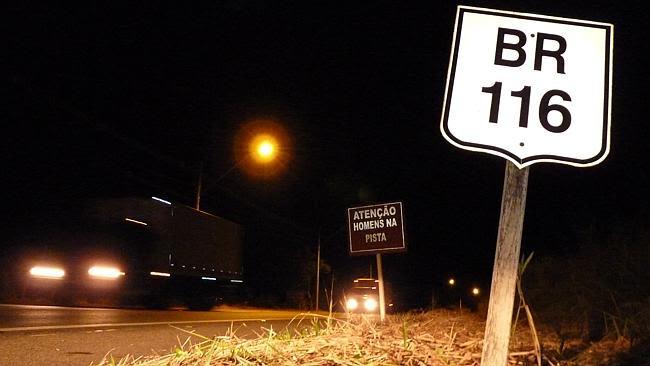

Matt Roper first got involved in Brazil while studying for his undergraduate degree in music. Getting involved in campaigning for human rights causes led him to find out about sex trafficking issues in the Amazon region of Brazil, and in 1997 he found himself travelling out to South America to work with street children in Belo Horizonte, Brazil’s third-largest city.

He spent a couple of years with a project which support both boys and girls who lived on the streets, before coming to realise that the girls were not really being catered for.

He said: “The social projects that existed for children and teenagers living on the streets were based on a model for boys, so the girls often felt left out, and didn’t have anything that attracted them away from the streets.”

The girls were often more addicted to the crack cocaine and other drugs than the boys, and emotionally attached to the street gangs and their controlling ‘boyfriends’, which stopped them from leaving the streets.

Matt said: “Their self-self esteem was so low because of being treated so badly, so they didn’t feel like they deserved anything else.”

The fate of these girls weighed on his mind, and he began to plan a new social project, just for girls, with activities and projects which were aimed at them, to attract them away from the streets - and that’s how Meninadança was born.

Along with his friend Warlei Torezani, he began to think about what kind of things would be a stronger pull for the girls than the things which were holding them prisoner on the streets.

He said: “Dance just seemed like an obvious idea. All girls love to dance, and it’s a way of building them up, helping them to recognise their own worth, helping them to find their potential, to believe that they’re beautiful on the inside, to do something beautiful. Through dance, they begin to see that they can achieve their dreams.”

They opened a centre, painted pink, with a dance studio, a beauty salon, a gym, and other activities and therapies which appealed to the girls. The girls named the centre Meninadança - literally, ‘girl dance’, and it was a huge success.

“It was a process for them, of feeling good, then achieving something - a goal they set, and then the aim, to help them realise that they deserved to leave the streets, that they deserve a better future, and empowering them through all these things to say no, and to choose to go after their dreams.

“Every day we would go to the streets, persuade the girls to come, and often they would come even with their ‘boyfriends’ telling them not to, they began to have that courage. Within weeks they were saying, ‘we don’t want to live on the streets anymore.’”

They opened residential homes, and by the time the first phase of Meninadança finished, in 2004, all the girls they had been working with had left the streets, with many even reconciling with their families and going home.

“Today, there are girls from that time who credit Meninadança with saving their lives.

I met a girl recently who I’d lost contact with - she was just the worst, hopelessly addicted to crack. I remember picking her up every morning, underneath a viaduct with men all smoking crack - a really dangerous place - and she started coming to the Pink House.

Very quickly the way that she looked at herself, and looked at her life changed, and she wanted to go home. I took her home on a bus - she came from another town, six hours away - and lost contact with her.

Last year, she got in touch with me again; she has two beautiful daughters, and she’s working, and she says ‘Meninadança saved my life.’”

“So we saw that the methodology, using dance, making the girls feel really special and that someone was thinking of them, doing things for them, was effective.”

Matt’s visa ran out in 2004, by which time as far as he knows, there were no street girls left in Belo Horizonte - an incredible achievement.

In 2010, Dean Brody, a Canadian country singer, got in contact with him. Dean had read Matt’s book, ‘Remember Me, Rescue Me’, and felt deeply touched.

Dean grew up in a small ranching town in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, where he worked at the sawmill by day, and sang country music to himself with an old guitar by night, dreaming of seeing his name in lights.

At 26, he and his wife, Iris, packed up and moved to Nashville, Tennessee to chase his dream, and four years later he got his first recording contract.

Dean and Iris had always felt a particular concern for young girls caught up in prostitution and human trafficking around the world, and Dean had promised to himself that if he were to become successful, he would use it to make a difference in the world.

He found a copy of Remember Me, Rescue Me, which Matt had written six years before on a farewell tour of Brazil in 2004, looking at the issue of child prostitution, and read it with a mix of heartache and horror.

Dean got to the last page during a flight to Nashville to record his second album, which would top the Canadian charts. Fighting tears, he wrote an email to Matt.

“It was surprising to me that Brazil had such a problem [with children involved in prostitution] and was ranked among the worst. Then I came across your book, and it broke my heart.”

Eight months later, Dean and Matt met in Canada, and decided to found charities, one in England and one in Canada, to raise funds for projects already in Brazil, the first a ‘favela’ project in Belo Horizonte which was helping to stop teenage girls falling into a life of prostitution and gangs.

Three months later, they met again in Brazil. They visited the project in Belo Horizonte, then set off on a road trip to Governador Valadares, a small rural town which Matt had visited while writing Remember Me, Rescue Me.

They were driving along the BR-116 when they had an encounter which changed their lives.

The cover of Dean Brody's album, 'Dirt', on which the song 'Leilah' appears.

The cover of Dean Brody's album, 'Dirt', on which the song 'Leilah' appears.

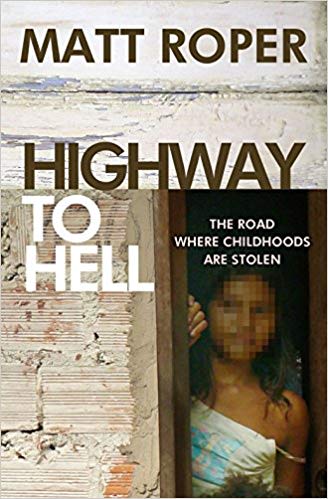

The cover of Matt Roper's book, Highway to Hell, which chronicles the journey he and Dean took up the BR-116, and the girls they met.

The cover of Matt Roper's book, Highway to Hell, which chronicles the journey he and Dean took up the BR-116, and the girls they met.

Dean was so moved by the encounter, he sat down and wrote a song.

He emailed Matt.

In his book, 'Highway to Hell: the road where childhoods are stolen', Matt recalls: "The song was a haunting, heartfelt ballad which brought the memories of our journey, and that first encounter with the girl in the lilac dress, flooding back."

Instead of heading back to Rio for a few days on the beach to end their visit to Brazil, Matt and Dean decided to drive on further up the BR-116.

They were determined to find out whether Leilah was just one, tragic case, or if there were more girls like her.

Matt recalls the decision in his book.

Medina is a tiny rural community, clinging to the side of the BR-116 highway. Matt and Dean arrived early in the evening, with no contacts in the town.

A local directed them to the town’s children’s councillor, essentially a social worker, named Rita.

She invited them in without hesitation, as soon as she heard of their mission.

Matt tried to explain why they were there.

“Rita, last night we met a young girl selling her body on the motorway. We decided to find out more. I don’t really know why we ended up coming here to Medina. I wondered if you might be able to help us…”

Rita paused, no longer smiling. Then she said:

Her voice trembled as she told them about the tragic situation in her town, almost too horrific to grasp. Hundreds of girls, forced by their own families into a life of humiliation and abuse; mothers who swap their own daughters for a bag of beans or a packet of cigarettes, girls aged twelve and thirteen dying of AIDS, and so many more whose fate she didn’t know, girls whom she had cared for, but who one day climbed into a truck headed north or south along the BR-116, and never returned.

That phrase would haunt them through the rest of their journey, coming back to them again and again, the image even featuring on the cover of Dean’s album, ‘Dirt’.

The next day, they met up with Rita again, and she explained more of the situation.

Matt recalled the words of the President of the Minas Gerais State Assembly, whom they had met in Belo Horizonte.

"You won't find a thing... that kind of thing doesn't happen any more."

Horrified, he asked Rita how it was that nobody knew, why it wasn't a national scandal.

She leaned forward.

That day, Rita introduced Matt and Dean to several girls in Medina who regularly sold their bodies on the motorway.

A nine months later, Matt quit his job at the Daily Mirror in London, and he and his family moved to Brazil permanently, settling in Belo Horizonte, the capital of Minas Gerais state.

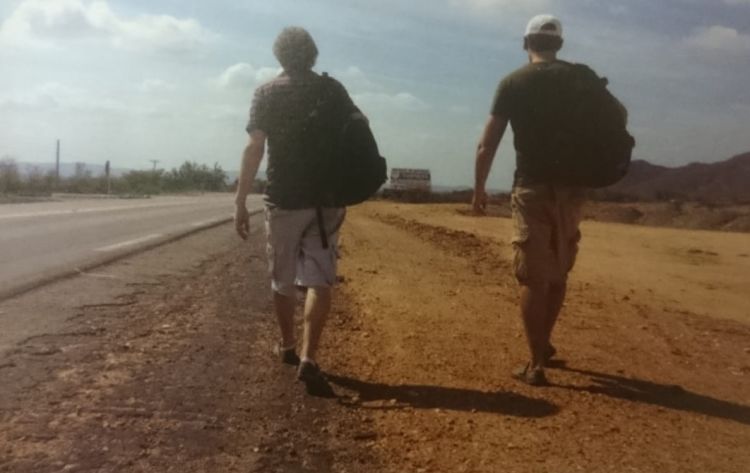

Dean flew in three months later, and together they set off on a 1,500 mile roadtrip, beginning again at Governador Valadares, where they had first met Leilah, and continuing all the way up the BR-116 to Fortaleza, on the northern tip of Brazil.

Matt details the stories of 29 separate girls in 'Highway to Hell', each more desperate than the last. These are just a few of them.

Sisters Rebeca (15) and Milene (12) live in 'The Chilli Peppers', the poorest a district of Salgueiro. Matt describes their street as 'the poorest, most pitiful place... a living hell of squalor and brokenness, baking in an insufferable heat.'

Fifteen-year-old Rebeca is already mother to two children, aged two and six months - both the products of 'programmes' - and Milene, just twelve, is already going out at night to pick up 'boyfriends' - her word - alongside her more experienced sister.

Milene recently had to call the police after a man paid for sex with her, but hadn't been able to penetrate, and began threatening to come back and 'finish the job'.

The sisters go out two or three times a week, but insist they look after themselves, and always use condoms. Rebeca is quick to add: "We're not prostitutes, though. We enjoy it."

Livia and Tatiane are best friends. They also live in the Chillies, down the street from Rebeca and Milene.

Twelve-year-old Tatiane lives with her parents in a two-room brick shack, right at the end of the road, which ends abruptly in a crocodile-filled swamp.

A shy girl, her favourite thing to do is 'drawing and colouring in', and she wears her hair neatly tied back.

At night, she wanders the dark dirt streets of the Chillies, selling her body for drugs and alcohol.

Her best friend Livia is just 10. She loves to play football with her friends on the street during the day.

At night, she too sells her body, flaunting her prepubescent figure in the seedy 'boteco' bars. If you ask her about it, she hides her face in her hands, the picture of a shy child.

14-year-old Natiele lived in Padre Paraiso.

She would go out every day to sell bunches of chives, bringing home the money to her mother, Roxa, each evening.

One night in 2004, she didn't come home.

A friend helped put her mother's mind at ease - she had gone to work in the home of a rich family, and would soon come back with her earnings, which would be so much more than the little she got from selling chives.

Four months later, Roxa got the devestating news that Natiele had been found dead, nearly 1000 miles away in the north eastern state of Rio Grande do Norte.

She had been brutally killed by a trucker; beaten over the head and shot. Her death certificate called it 'an extremely violent death'.

No-one knows exactly what happened to her in those four months, but the woman who lured her away is known to run brothels, and specialise in kidnapping underage girls.

The shock of Natiele's death caused Roxa's body to shut down. Paralysed on one side, she no longer left the house, but sat inside in the dark.

She burned all the photos of Natiele, because she couldn't bear to see her daughter's face.

They never caught the trucker who killed her, and the woman who kidnapped her is also still free, though everyone knows who she is.

Poliana, 12, lives in Medina. She is Lilian's cousin, and lives across the road from her.

She was a chatty, playful child, until her aunt took her and her sister to a place called Veredinha, fifty miles north of Medina.

The small town is little more than a huge truck stop with row after row of bars and brothels, and it is notorious for is particularly high incidence of child prostitution.

She and her four sisters were often beaten by their mum's abusive, drunk boyfriend, sleeping in the outside toilet to get away from him, so she was probably pleased to get away with her aunt.

In Veredinha, though, something happened to her which left her sitting huddled, biting her nails and staring into the distance, a shadow of her former self.

Matt and Dean walking along the BR-116, near Salgueiro. Image from 'Highway to Hell', used with permission.

Matt and Dean walking along the BR-116, near Salgueiro. Image from 'Highway to Hell', used with permission.

Sisters Rebeca, 15 and Milene, 12, from the Chilli Peppers in Salgueiro. Image from 'Highway to Hell', used with permission.

Rebeca and Milene

Livia, 10, and her best friend Tatiane, 12, from the Chillies. Image from 'Highway to Hell', used with permission.

Livia, 10, and her best friend Tatiane, 12, from the Chillies. Image from 'Highway to Hell', used with permission.

Dean comforts Roxa, the grieving mother of 14-year-old Natiele, in Padre Paraiso. Image from 'Highway to Hell', used with permission.

Dean comforts Roxa, the grieving mother of 14-year-old Natiele, in Padre Paraiso. Image from 'Highway to Hell', used with permission.

12-year-old Poliana, from Medina. Image from 'Highway to Hell', used with permission.

12-year-old Poliana, from Medina. Image from 'Highway to Hell', used with permission.

Meninadança

Before they left on their roadtrip up the BR-116, Matt and Dean had spoken to Rita about setting up a new phase of Meninadança, the methodology for reaching girls which had proven so effective in Belo Horizonte 14 years before.

By the time they got back, she had found a house in Medina, and painted it the brightest pink she could find.

It turned out to be an excellent marketing strategy - the bright pink building attracted the attention of the curious locals, who all wanted to know what it was for. They dubbed it 'casa rosa' - the Pink House - and the name stuck.

Rita organised a cocktail party for the great and good of Medina - everyone from the mayor to the head teacher of the local school - and they all turned out for the event. Matt explained their plans, and Dean, who had flown in specially, sang for them, to rapturous applause. Many people pledge their support for the project - including the mayor, who pledged to donate a thoroughbred horse worth a significant amount of money!

Over in England and Canada word was spreading too, and people were being sponsored to walk 116 miles, or lose 116 pounds, or give something up for 116 days, to raise money for the cause.

With pledges of support in place, planning began in earnest.

This new phase of Meninadança would have five branches.

First and foremost, the Pink House would work directly with the girls. An all-female space, the house would provide a sanctuary, a place to learn, grow, and dream, as well as provide counselling and support.

The Changing Minds programme would set out to work in the community, to shift the ingrained culture of abuse. From public dance shows to protest marches, it would seek to challenge the acceptance of child prostitution, and present the girls as children to be protected, and people to be respected.

As well as the all-female team working with the girls, Meninadança would have an office in Belo Horizonte, headed up by Matt. The team there would seek to promote the work of the charity nationally and internationally, both to raise funds, and also to make the epidemic of child prostitution an internationally know problem, and force the country to take it seriously.

A legal team would be set up, to take on the injustice and corruption. Many of the girls had reported their abusers, but they were never arrested or charged; this team would seek to change that.

And finally, a team would put together resources and conduct training for other charities and people working with at-risk girls, seeking to spread the ethos and success of Meninadança to other areas with similar issues.

With the Pink House being set up, Rita and her began befriending the girls they knew were caught in a world of prostitution.

Slowly, they won their confidence and trust, playing games with them, taking them out for milkshakes, even baking cakes with them, or simply sitting in the square at night and chatting.

Word got out among the girls that there were people who cared, who were fun to be around, who would listen.

They began knocking on Rita's door, trying to figure her out, and slowly began opening up and sharing their hurt and fears.

When the Pink House was ready, replete with dance studio, beauty salon, and other rooms for craft and activities, Rita and her team visited the home of every girl, to deliver a personalised pink invitation to enrol at the Pink House.

They gave out 48 invitations, with no idea how many - if any - would turn up for registration the following week.

Matt described the opening of the house in 'Highway to Hell':

Those 48 girls included Lilian and Poliana, whose stories are included above. Today, they are both flourishing in their new environment, back in school, and with bright futures ahead.

With the house open, they needed staff. Some were recruited locally, but others volunteered from further afield. Holly Eves came from Ireland to work on the project, eventually staying for four years.

With the Pink House open, Matt moved on to the next project.

First, the office in Belo Horizonte opened in 2014, to coordinate the Pink House project as well as promote awareness raising, advocacy and educational campaigns.

The campaigns were many and varied, and within year they had seen great success.

In November 2015 they launched a campaign to catch Joel Cruz, the former mayor of the town of Taiobeiras, who had fled justice after being accused of using his wealth and power to abuse hundreds of young girls over three decades.

At Meninadança’s prompting, 700 people from across the globe wrote letters to the town's police chief asking for more to be done, eventually reaching the state's highest police authority, which designated an investigator to track Cruz down.

He was finally arrested in April 2016, and received a prison sentence of over 26 years in jail, in December.

The global force of letter-writers was named ‘Project 116’, and has since been mobilised for other projects.

Meninadança took on the case of Emilly, a nine-year-old girl from Medina who was raped and murdered in January 2014. Their legal team represented Emilly’s family in court proceedings, and secured a conviction of 26 years' jail for her killer.

In 2016, their campaign to honour her memory resulted in Medina's council establishing a official day of fight against sexual exploitation every December 9, Emilly's birthday, and the renaming of a public building after her.

After discovering that 658 children - that’s one in ten children - in Medina had been victims of violence which was reported to the police in just 10 months, the team organised a public protest called ‘We Will Not Be Silent’ in 2016.

The team brought Medina to a standstill as hundreds of young people took to the streets to protest against violence and abuse.

They wore badges and black tape over their mouths, and stood silently in front of Medina’s key buildings; the council chambers, police station, and the courts of law.

At the town’s main square, they laid 658 white roses on the ground, one rose for each victim.

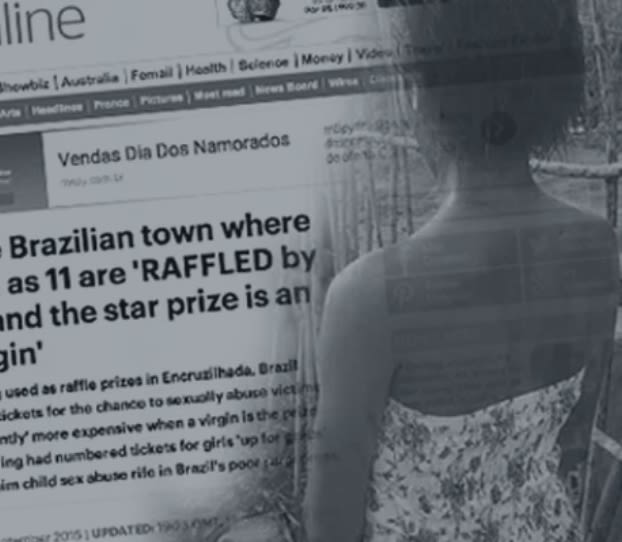

In September 2015, the team discovered that young girls were being offered as prizes in raffles in the small town of Encruzilhada, near Cândido Sales.

Following their investigation being published in the UK's Daily Mail, the story was picked up by Brazil's biggest news vehicles and led to an investigation by the state human rights secretariat, and the raffles being stopped.

In July 2016 a team from Meninadança walked the 100km from Medina to Cândido Sales, through the BR-116's 'child prostitution belt'. They tied a pink ribbon to every km sign, as a symbolic act to show the region that young victims of abuse and prostitution are no longer alone.

At the same time a team of 25 people went to every gas station, truck park and community along the highway, giving out stickers and fridge magnets which read 'I am against child sexual exploitation' and cards telling people how they can report abuse.

In 2016, a team began working part time with girls in Cândido Sales, Bahia state. Shortly afterwards, they opened second Pink House in the town.

It was the first social project of any kind to ever be established there, and today works with nearly 100 girls.

'Your Look Can Transform Our Lives' was a street art project created to challenge the way teenage girls are seen by residents of Medina.

The team took an abandoned wall and transformed it into an eye-catching mural, including dozens of ‘eyes’, each painted by one of our girls.

The town was invited to an unveiling event, where the girls danced, read poetry and invited townspeople to look at them differently, not as worthless objects, but as potential and hope for the future.

In Brazilian popular culture, the word 'novinha' - literally 'little girl' - has come to mean an adolescent as an object of sexual gratification.

One morning in 2017, residents of Medina woke to find the town filled with banners and posters which read: 'You know that novinha? We call her a child'.

These were hung at key points around the town, including at the entrance to every local school.

The phrase uses a lyric from a popular funk music song and strikes deep into the heart of a local cultural acceptance of abuse of children and teenagers.

In September 2018, the team signed paperwork for a new Pink House in the town of Padre Paraiso.

The house has been leased to them free of charge for 10 years by another charity working in the town.

Back in Medina, Bia was one of the girls attending. Now, she works there, teaching the girls how to use the beauty salon. Here is her story.

The Medina Pink House

The Medina Pink House

The Mayor of Taiobeiras

The Mayor of Taiobeiras

Emilly

Emilly

We Will Not Be Silent

We Will Not Be Silent

The Encruzilhada raffles

The Encruzilhada raffles

Matt and Lorene, 36km into the 100km walk

Matt and Lorene, 36km into the 100km walk

A street in Cândido Sales

Primavera district, Candido Sales

'Your Look Can Transform Our Lives'

'Your Look Can Transform Our Lives'

We call her a child

We call her a child

Warlei and Sonia, signing the paperwork for the Padre Paraiso Pink House

Warlei and Sonia, signing the paperwork for the Padre Paraiso Pink House

Tell My Story

A documentary about Meninadança and the BR-116

In September 2018, the team from Raiz Films went out to Brazil to begin filming for the documentary.

They are still crowdfunding to cover the costs of post-production (http://igg.me/at/tellmystory).

The documentary follows a group of girls from the Medina Pink House, as they develop and then perform a piece of theatre, under the guidance of theatre specialist Francine Kliemann.

The piece will be filmed, then screened to the girls and their families.

The documentary will interweave scenes from the theatre piece and the screening with the girls' own stories, written down by the film crew and read out by actors, to protect their identities.

Uncovering the Truth

The latest updates from Meninadança and the Tell My Story team

On September 26th, 2018, the Raiz Films crew witnessed an older girl being prostituted by her mother.

The shocking footage was shared to social media, where it was viewed more than 3000 times in the first 48 hours.

It shows a 19-year-old girl being pimped out by her mother, who flags down a truck before putting her daughter inside then waving her off. The girl, who the Meninadança team were able to identify from the clip, has been sold by her mother in this way since she was young, to help her poor family put food on the table.

Joseph Ferreira Campos, director of Raiz Films, said: "We knew this was happening, but to see it and catch it on film, including the casual way her mother waves to her - despite not knowing if her daughter will ever return - was heartbreaking."

On September 26th 2018, Meninadança launched a new iteration of Project 116, the army of letter-writers from around the globe.

They are asking for their help to catch a rapist, who believes he will never have to pay for his crimes.

Luiz Gonzaga Gonçalves, a taxi driver in Cândido Sales, lured one of Meninadanca’s girls into his vehicle along with her friend, last year.

He drugged her, took them to a deserted dirt track, and raped her in front of her young friend, before dumping them on the outskirts of town.

The girl eventually made it home, very distressed, half naked, her clothes torn.

The girl’s mother reported the crime, and the children’s councillor took the girl for a rape kit exam, which was sent to the town prosecutor.

The judge issued an arrest warrant for Gonçalves based on this evidence, but the police never arrested him.

This was more than a year ago. The police never arrested Gonçalves. In fact they never interviewed him, or even went to his house. He violently raped a young girl, in broad daylight, and despite evidence and a witness absolutely nothing happened to him.

The photo on the right shows the moment the girl broke down as she told one of the Pink House staff about the rape.

Meninadanca have since discovered that a relative of Gonçalves works at the police station, and has ensured that the investigation ground to a halt.

They are marshalling Project 116 again to send ‘an avalanche of letters’ to the police chief in Cândido Sales, with people all around the world demanding that justice be done and calling on him to ensure that Gonçalves is arrested.